We live a few blocks from the Minnesota State Fairgrounds, and every summer the “Back to the Fifties” car show is held there. There’s usually no need to actually pay to get into it to see the cars—our neighborhood is full of them, cruising around, for the duration of the show. But lately I’ve paid to get in, mainly to get shots of the nameplates, or “brightwork” as it is known.

The Chevy “Bel Air” nameplate, from the late-fifties, is my all-time favorite. The design is so simple and stylish. (Photo taken in Saint Paul, Minnesota, June 20, 2009.)

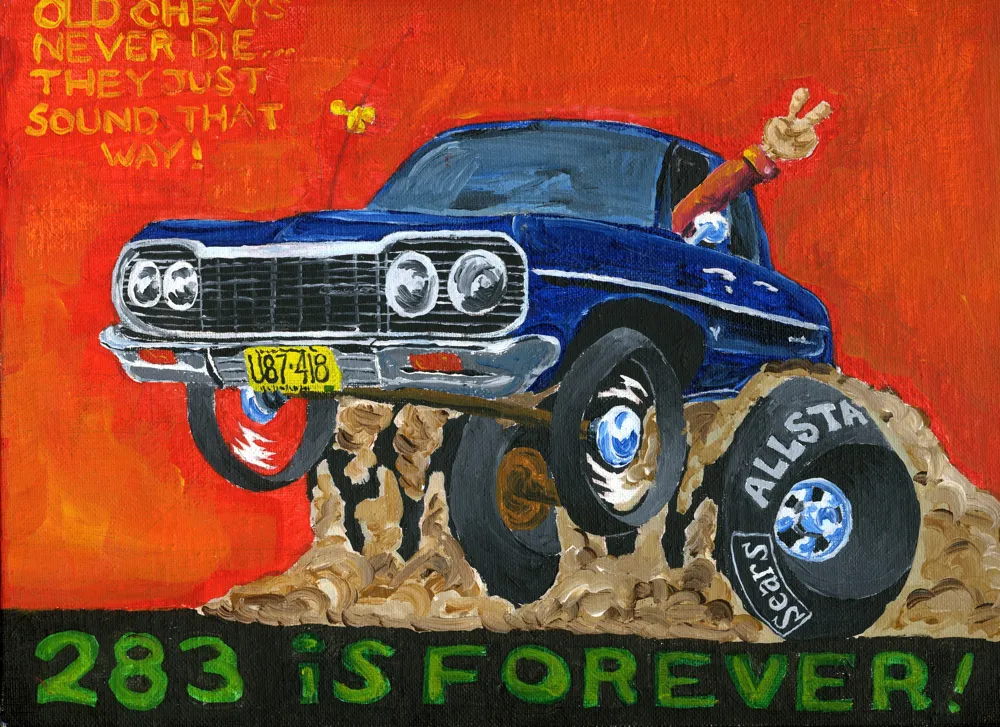

There might be a personal bias to my “Bel Air” preference. We always had Chevys when I was a kid, a ’59 Bel Air and a ’64 Bel Air—the car I learned to drive on and the car I drove during high school in the early seventies. Here’s a cartoon painting I did of it back then as a joke:

(When I was in high school, I had a little side business doing cartoon drawings of cars like this for my friends. I’ll post more of them sometime.)

When I bought this computer in 2006, I did’t expect to still be using it in 2012. It hasn’t always been my primary machine, but it’s been in use one way or another all that time.

Apple has used essentially the same case design even longer, going back to the Power Mac G5 in 2003. I had one of those, too, and it was kind of a dog. This one is the first generation Mac Pro, which was released when Apple switched to Intel processors. I chose the mid-range model, with two 2.66 GHz Dual-core Xeon processors, a 250 MB hard drive, and 1 GB of RAM.

It was my main machine for several years, with a 15” MacBook Pro as a secondary machine for taking work on the road. Eventually, having to keep my work sync’d between them was too much trouble and I switched to a 17” MacBook Pro for everything. I retired the Mac Pro to the basement, using it as a server and for watching movies or playing music, and other non-work-type things.

About a year ago, I changed my mind. The 17” was too much of a compromise—not that powerful as a desktop machine, and it rarely left my desk, unless I was traveling. So, I got a MacBook Air and a 27” iMac. What made it possible? In a word: DropBox.

This setup worked great, but recently, the iMac started giving me the worst possible kind of trouble—kernel panics during backups. I still don’t know what the cause is, but I couldn’t trust it as my main machine anymore.

Long story short, I brought my old Mac Pro out of retirement. After upgrading the video card, hard drives, software, display and memory, it’s never run better. It’s smooth and quiet and plenty fast enough for my needs.

One of the things that made me reconsider it was a discussion sometime last year on Hypercritical, John Siracusa’s weekly podcast. Unfortunately, I don’t recall which show it was, but basically Siracusa pointed out one of his reasons for preferring Mac Pros over iMacs and portables: External hard drives usually have cheap power supplies. I can attest to this, having several fail on me over the years. The Mac Pro, however, has a very robust power supply and therefore hard drives you add to it are much more reliable, another thing I can attest to. I had never really thought about this before, and had even tended to use external drives with my Mac Pro. But it made a lot of sense, and now I’m sticking to internal hard drives for everything.

I’m very happy with this setup. I’ve got a really solid desktop machine now, and the MacBook Air is my all-time favorite laptop. And DropBox makes it easy to work with two machines. The most amazing thing to me is that this Mac Pro is so old and yet it has no trouble running the latest software. I’d say it was a pretty good deal.

Gee, they make it seem like a good thing.

This was actually for something that was used in shoe stores back in the forties. People put their feet inside an x-ray machine so that they could have their feet “scientifically” measured for shoes. That was before they realized how dangerous it was.

Seen in a museum in Madison, Wisconsin, March 30, 2010.

Earlier today I watched this wonderful presentation by Jeremy Keith that he gave at the Build conference. He touches on something I’ve thought about for a long time, going back even before personal computers: The long term prospect of the media we record things on—paper, records, magnetic tape, film, video tape, floppy disks, compact disc, DVDs, hard drives and servers.

I had almost the same thought as Jeremy: I picture archaeologists in the distant future studying what remains of our culture and finding lots of documents and records right up until around the end of the twentieth century—and then almost nothing that can be read or decoded.

Printed books, artwork, typed and written manuscripts, photos on film and paper, with all of these media, you can either read and decode it directly with your eyes. It may be faded or fragile, but if it survives, whatever is recorded on it will survive. Even movies on film and phonograph records could be reverse-engineered just by using observations and common sense, even if some of the nuances may be lost.

Then you get to magnetic tape. If you’ve never seen it before, it’s not obvious what it is, and even if you guessed correctly, the magnetic signals on the tape fade over time and the tape itself deteriorates.

Things start getting really bad when you go to analog video tape. To even make sense of what’s on the tape—assuming you figure out that it’s some kind of motion picture medium—you would need to reinvent the television and video tape player. Very difficult, but conceivable.

All bets are off when you get to digital storage, which Jeremy gets into in detail in his presentation. To me, it seems that it would be nearly impossible to recover anything stored digitally if, in some cataclysm, the knowledge of computer technology was lost.

Even things from the recent past are getting difficult to access. I switched to digital tools for most of my design and artwork in the late 1980s. Some of the work I did—in the form of PageMaker files, for example—I would have a difficult time retrieving. Yes, technically, much of this stuff can be accessed if you have old enough hardware and software. But hardware doesn’t last forever, and what about more recent software that requires internet activation?

When I look back through my old artwork, I have less and less in the form of physical objects—drawings, photos, printed samples. Physical objects get old, faded, and damaged, but you can still hold them, and look at them. Digital stuff never gets old or faded, but if even a few bits of data are corrupted, an entire file or disk can be lost forever, even if you still have something to read the media.

Then I think, who cares, other than pack rats like me? I thought the same thing watching Jeremy’s talk. Sure, huge amounts of digital culture may be—probably will be—lost to the future. But remember, there are many things from the past that are lost to us now because they happened before sound and picture recording—musical performances, theatrical performances and speeches, historical events. But lots of stuff did survive and will survive. We still print tons of books and magazines (so far). People still keep journals and diaries, and artists still keep sketchbooks.

Ultimately, culture is for the living. If it survives to be studied and appreciated by people in the future, great, and I hope it does. If not, I’m sure they’ll be busy making their own anyway.