Reader Dan Madden is a fan of my Pangrammer Helper, a little Flash application I made that helps in the creation of pangrams. (A pangram is a sentence or phrase which contains every letter of the alphabet.) He and his family had so much fun with it that it prompted his brother, an english professor at BYU in Utah, to hold a “Pangram Haiku Contest” with his students. Here are some of the results:

Lost in flight, quiet.

Yellow jacket reproves me.

Vexed, I buzz away.

Mosquito buzzes

around jackal’s furry paw.

So vexing, that bug!

Read ye my haiku!

Strong, living words dazzle. Jump

back, quietly fixed.

Haiku verses flow

like a bad, exacting quiz.

Too jumpy, yet fun.

The ax swerves, tree dies:

Quite a lop job, so crazy.

Man kills for nothing.

Wise raven in tree

Spies sly fox dozing. Gives him

Loud quack. Bejeezus!

Your quick wit doesn’t

Faze me. I can’t help your jive!

Go back to de-tox!

Pangrammer Helper 2.0 is a new version of the pangram-making utility I created in 2005. The new version adds the ability to keep track of how many times each letter of the alphabet is used in your pangram. (Thanks to Scot Ober for the suggestion.)

In case you don’t know, a pangram is a phrase or sentence that uses every letter of the alphabet at least once. The most common one in English is “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.” Here are a few pangram links for more examples and information:

P22’s 2004 Pangram Contest Winners

The Pangram Page (dead link)

Pangram Discussion on Typophile.com

NPR Sunday Weekend Edition 2002 Pangram Contest Results

Earlier today I watched this wonderful presentation by Jeremy Keith that he gave at the Build conference. He touches on something I’ve thought about for a long time, going back even before personal computers: The long term prospect of the media we record things on—paper, records, magnetic tape, film, video tape, floppy disks, compact disc, DVDs, hard drives and servers.

I had almost the same thought as Jeremy: I picture archaeologists in the distant future studying what remains of our culture and finding lots of documents and records right up until around the end of the twentieth century—and then almost nothing that can be read or decoded.

Printed books, artwork, typed and written manuscripts, photos on film and paper, with all of these media, you can either read and decode it directly with your eyes. It may be faded or fragile, but if it survives, whatever is recorded on it will survive. Even movies on film and phonograph records could be reverse-engineered just by using observations and common sense, even if some of the nuances may be lost.

Then you get to magnetic tape. If you’ve never seen it before, it’s not obvious what it is, and even if you guessed correctly, the magnetic signals on the tape fade over time and the tape itself deteriorates.

Things start getting really bad when you go to analog video tape. To even make sense of what’s on the tape—assuming you figure out that it’s some kind of motion picture medium—you would need to reinvent the television and video tape player. Very difficult, but conceivable.

All bets are off when you get to digital storage, which Jeremy gets into in detail in his presentation. To me, it seems that it would be nearly impossible to recover anything stored digitally if, in some cataclysm, the knowledge of computer technology was lost.

Even things from the recent past are getting difficult to access. I switched to digital tools for most of my design and artwork in the late 1980s. Some of the work I did—in the form of PageMaker files, for example—I would have a difficult time retrieving. Yes, technically, much of this stuff can be accessed if you have old enough hardware and software. But hardware doesn’t last forever, and what about more recent software that requires internet activation?

When I look back through my old artwork, I have less and less in the form of physical objects—drawings, photos, printed samples. Physical objects get old, faded, and damaged, but you can still hold them, and look at them. Digital stuff never gets old or faded, but if even a few bits of data are corrupted, an entire file or disk can be lost forever, even if you still have something to read the media.

Then I think, who cares, other than pack rats like me? I thought the same thing watching Jeremy’s talk. Sure, huge amounts of digital culture may be—probably will be—lost to the future. But remember, there are many things from the past that are lost to us now because they happened before sound and picture recording—musical performances, theatrical performances and speeches, historical events. But lots of stuff did survive and will survive. We still print tons of books and magazines (so far). People still keep journals and diaries, and artists still keep sketchbooks.

Ultimately, culture is for the living. If it survives to be studied and appreciated by people in the future, great, and I hope it does. If not, I’m sure they’ll be busy making their own anyway.

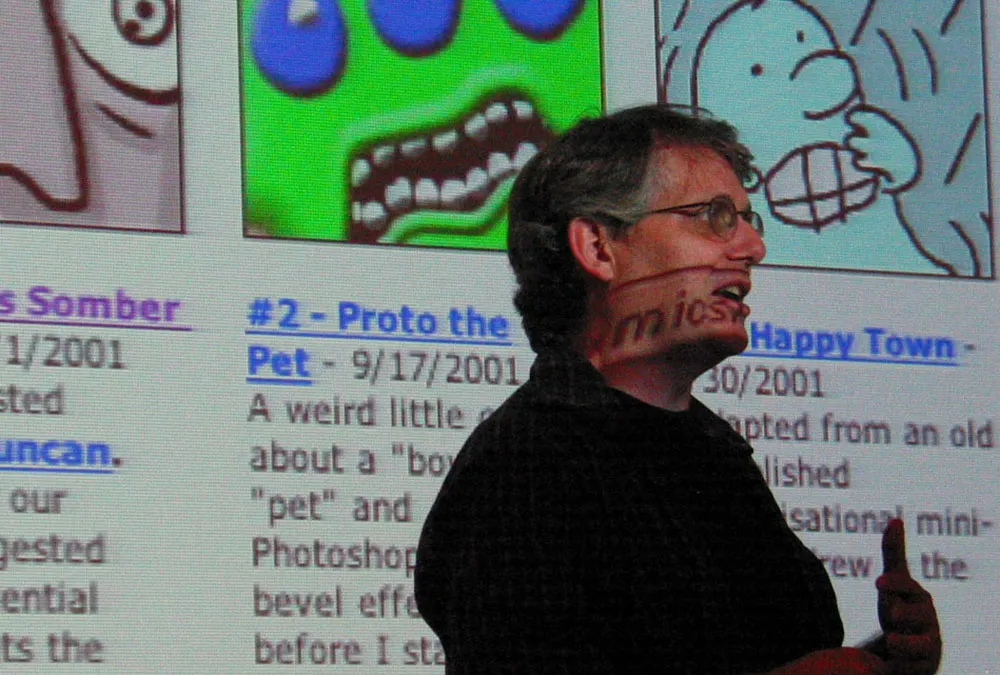

I spent last evening enjoying a talk by Scott McCloud at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. He did a similar talk there two years ago which I also attended.

McCloud is a comic book artist and writer best known for his book Understanding Comics. He talked mainly about online comics, a phenomenon he has been involved in since the beginning.

The audience was mainly hard-core comics people, so it felt a little weird for me to be there. When I was young, I read Mad magazine and wanted to be a cartoonist for a while. But I’ve only been into comic books sporadically.

McCloud’s book caught my attention a few years ago and I would put it on my short list of most inspiring and thought-provoking books. The reason is that I just like the way McCloud thinks.

He has a knack for getting beyond conventional thinking, drawing out fundamental principles and presenting them lucidly. It’s an old cliché to say someone “thinks outside the box.” In McCloud’s case, I wonder if he even remembers what the inside of the box looks like.

Anyway, it was a lot of fun. As with the last time I saw him talk, he had his family with him. And, once again, he did a dramatic reading of Monkey Town at the urging of his two young daughters (only this time he didn’t blow out any of the speakers in the auditorium). And I got him to sign my copy of Understanding Comics. Pretty cool.

Flash animation designed to promote my typeface Sharktooth. Note that there are some working links visible under the glass. Like the Coquette Clock, the entire file shown here is very small at just over 11k. Created in 2001.

Note: Flash 5 or later plug-in required to use loupe.

Some time in the last year or so, I bought, through Amazon Books, Paula Scher’s book Make It Bigger, a beautiful overview of her outstanding career as a graphic designer. If you’ve ordered books through Amazon and haven’t opted out of their periodic mailings, you regularly get recommendations for other books in which you might be interested, based on your previous purchases. It usually comes up with reasonable suggestions, but take a look at the one I received the other day:

We’ve noticed that customers who have purchased books by Paula Scher often purchased books by Peter Hall. For this reason you might like to know that Peter Hall’s newest book, Understanding Disease: A Centenary Celebration of the Pathological Society, will be released soon. You can pre-order your copy by following the link below.

I guess there must be more than one author named Peter Hall.